Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Amy Gardner at the Washington Post got the scoop. In an hour-long telephone call to Georgia officials, including the the secretary of state, Trump browbeat them and hinted around that he could arrange jail time for them or foment unrest or spoil the January 5 senatorial run-off unless they found him enough votes to overcome Joe Biden’s slim lead in the state.

Former Obama acting solicitor general Neal Katyal said that Trump was talking like an organized crime boss, and I had the same thought. The heavy atmosphere of threat, the pointed question “how are we going to make this right,” the baseless assertions of owning something that didn’t belong to him, all made Trump sound very much like a wannabe Godfather.

Preet Bharara and others suggested that the president had committed “criminal solicitation” of election fraud both under federal and Georgia statutes.

Conservative Washington Post columnist Jennifer Rubin titled her op ed on the affair, “It’s impeachable. It’s likely illegal. It’s a coup.”

What does it mean for this telephone call to be a “coup,” and why do we call it that?

The term “coup” is short for the phrase coup d’état (koo day taah) which comes into English from the French for “blow to the state.”

In its meaning of a sudden change or overthrow of government it is a nineteenth-century borrowing into English, I think mainly from the 1850s. The Oxford English Dictionary gives two examples in that century:

1811 Duke of Wellington Dispatches (1838) VIII. 352 “I shall be sorry to commence the era of peace by a coup d’état such as that which I had in contemplation.”

1859 T. P. Thompson Audi Alteram Partem II. xcviii. 87 “A coup d’état as effectual for the time as that of Louis Napoleon [2 Dec. 1851].”

T. P. Thompson was a Radical member of parliament who was upset that the conservative prime minister, Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, the Earl of Derby, dissolved parliament. He saw it as a ploy to avoid having the elected legislators exert influence over the foreign ministry. This was at a time when war seemed on the verge of breaking out between France and Austria over the Italian nationalist movement led by Cavour and Garibaldi. He referred to the Executive sidelining the Legislature on a matter of foreign policy as a coup d’état, comparing Derby’s actions to the 1851 coup in France.

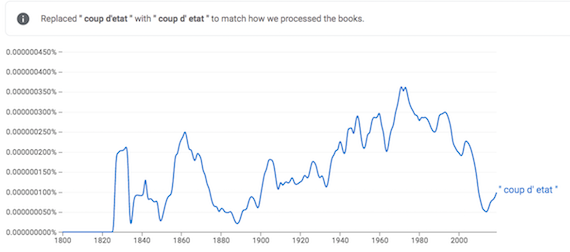

This citation points to the importance for the adoption of the term into English of the 2 December 1851 self-coup undertaken by Charles Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon I. Bonaparte was already president, but faced going out of office in 1852, and to stay in power, he made a coup d’état and styled himself Napoleon III. You can see the big spike in the use of the phrase (in all languages) in the wake of his coup in this Google Books ngram:

Courtesy Google Books Ngram viewer.

Karl Marx had a poor opinion of Louis-Napoléon, and the coup inspired him to observe archly, “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

That is, the uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte, was an example of tragedy. The nephew was just laughable. He was supported by the rich who delegated him to do his emperor schtick on their behalf. He also attracted the allegiance of street riffraff who lacked a real blue collar job and attendant stable class interests, and who therefore shifted politically here and there, open to the blandishments of the clown-in-chief.

With Trump’s attempted coup d’état in his Saturday telephone call with Georgia officials, we have now entered yet a third Hegelian appearance, this time in the form of a sinister organized-crime buffoonery.

Louis-Bonaparte’s coup signaled the death knell of the democratic revolutions of 1848 and was viewed with alarm by progressives. The abolitionist MP from Martinique, Victor Schoelcher, denounced the Second Empire and warned Britain against allying with it, lamenting that Bonaparte had bribed the generals to let him come to power.

An essay in The American Whig Review that appeared not long after Louis-Napoléon’s coup d’état satirized the possibility of an American coup. I presume the subtext here was the presidential race between Whig nominee Gen. Whinfield Scott and Democratic Party standard bearer Franklin Pierce. Pierce won fair and square, even garnering both the electoral college and the popular vote.

So we’ve gone in America, from light-hearted satire about it happening over here to a concerted attempt to make it happen.

—–

Bonus video:

Washington Post: “Audio: Trump berates Ga. secretary of state, urges him to ‘find’ votes”

© 2024 All Rights Reserved

© 2024 All Rights Reserved